Loggerheads and Leatherbacks and Sharks, Oh My!

Murphy circles the room to aid students with finding information. “Recognizing anomalies and trying to figure out why there is an anomaly is important when looking at the data from the research,” said Murphy.

October 12, 2016

Marine Biology Students Construct Migration Tracking Projects

“Look how far this little nugget goes!”

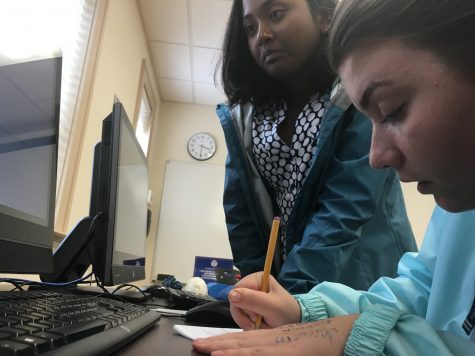

That’s how Sydney Schmidt (’17) responds as she and her partner Stuti Potnuru (’18) analyze the migration patterns of their new project subject, a sturdy female leatherback sea turtle named Lady Aurelia.

Each year the marine biology students craft a report and five-minute slide show presentation on the movement of a marine creature, typically either a shark or a sea turtle, and present their conclusions about the animal’s migration pattern in front of the class.

“We’ve been learning about why marine animals migrate and what factors pushed them to do so, such as temperature, salinity, bathymetry (depth), chlorophyll present, currents, and migration of prey. The main question is why our animal chose that specific route and then to make it even more interesting we have to explain where it will go next based on the factors’ maps that we must include,” said Schmidt.

Rad Murphy, Bolles’ marine biology teacher, explains that the most toilsome aspect of the migration project is connecting the dots between all the information.

“The part that students have trouble with most is summing all the information up into one synthesized conclusion. It can be overwhelming because they are using thousands of miles worth of maps and trying to solve a puzzle based on one specific animal,” said Murphy.

“As long as they come up with logical inferences and put effort into it then it’s fine with me and I’m proud,” continued Murphy.

Students use online resources, their notes, as well as Murphy himself to fashion the migration project. Due to the internet’s vast and sometimes somewhat ambiguous sources, many students often utilize Murphy’s help in class. “We google sites that use .edu or .gov endings but sometimes the maps are just plain hard to look at so I’ll ask Mr. Murphy,” said Schmidt.

Schmidt joked about the approachable teacher, “You know because he’s just sooo hard to talk to.”

Although the migration project requires students to process information on a deeper analytical level, the atmosphere in the classroom is bubbly, productive, and inquisitive.

“Learning why marine animals, turtles in our case, travel and return back to their birth places is really interesting. It’s pretty cool to think that they know where they come from and where they’re going,” said Potnuru.